Now Reading: The sweetness they don’t show in the video

-

01

The sweetness they don’t show in the video

The sweetness they don’t show in the video

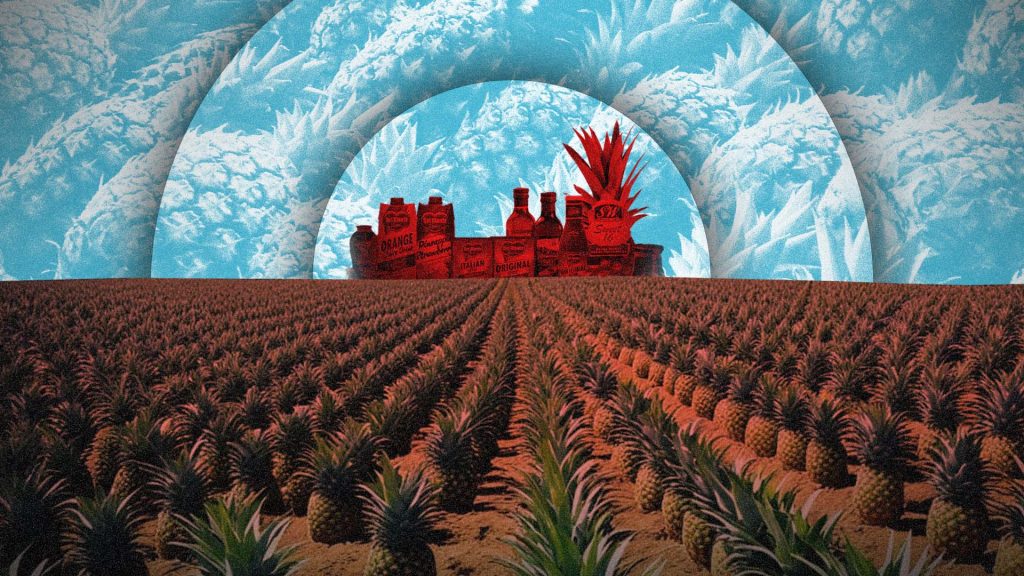

A recent corporate profile opens like a promise: neat homes, smiling workers, and the kind of benefits most Filipinos can only dream of: free housing, free water, free electricity, scholarships, hospital coverage. At first glance, Del Monte Philippines Inc. (DMPI) seems to be building a small utopia in Bukidnon, a company carefully curating the image of a workplace that nurtures and rewards its people.

The video that appeared on feeds raises immediate questions. The benefits it showcases might be real for some, but anything that looks that clean, polished, and perfectly timed rarely tells the whole story. Centennial celebrations, the Christmas season, and a feel-good profile from a respected journalist. When everything aligns this neatly, it is not coincidental. It is carefully crafted PR.

Camp Phillips didn’t grow out of corporate goodwill. It sits on land that once belonged to farmers, indigenous communities, and agrarian-reform beneficiaries—people who ended up leasing their own land back to Del Monte through “agribusiness venture agreements.” In the early 2000s, some farmers earned as little as ₱5,150 per hectare per year, with half of it going straight to amortization, leaving about ₱429 a month in real income.

When the choice is between giving up land or sinking deeper into debt, “cooperation” stops being voluntary. Pineapple monocropping only makes it worse, as studies link intensive plantations to erosion, biodiversity loss, and long-term soil nutrient depletion. Del Monte may provide housing, utilities, health benefits, and schooling, but these perks raise a question. Are they gifts out of generosity, or the price of acquiring land cheaply?

This is why the Davila video works the way good PR always does. It tells you where to look. It compresses a century of conflict, dispossession, and uneven power into a single narrative of a benevolent employer “uplifting” its people. But other reports complicate that sanitized picture.

In 2019, Global Witness linked Del Monte growers to incidents of violence against Lumad land defenders, a reminder that “development” often advances through intimidation and erasure. In Misamis Oriental, the company secured a lease to 226 hectares of “idle government land” for more pineapple and papaya plantations, raising alarms among environmentalists and small farmers already struggling for access.

In Bukidnon, agrarian-reform beneficiaries are still tied to decades-old leaseback contracts that many say undo the very gains agrarian reform was supposed to provide. These contracts are the hidden cost behind the glossy stories of “corporate generosity.”

There is nothing wrong with telling positive stories; workers who genuinely benefit deserve recognition. But Del Monte’s welfare package is framed as charity rather than a strategic exchange built on a long, messy history of land, power, and extraction. Emotional warmth and a “100 years of nourishing the nation” celebration can make viewers forget who actually bore the cost. A corporation that built its empire on cheap land, cheap labor, and depleted soil now draws applause for providing the very services its presence made necessary.

If Del Monte wants to talk about generosity, the full story must be told. How many farmers lost land through leaseback schemes? How much does the company earn per hectare compared to what farmers receive? What guarantees that future expansions won’t repeat past harms? Housing, water, power, and healthcare are welcome, but they do not erase the structural inequalities that let Del Monte prosper while many of its “partners” remain one disaster away from debt.

The goal is not to attack a single video or shame those who shared it. The goal is to stop letting corporations define kindness. Giving a house while taking land, paying for electricity while controlling livelihoods, sending children to school while leaving soil barren is not generosity. It is a transaction. Unlike videos, transactions do not end with warm lighting or music. They linger in the land, in what was taken, and in what communities are still fighting to reclaim. Funny how the sweetest stories always taste different when you know what was taken to make them.